Why Triangles?

Why is the math curriculum so concerned with the Pythagorean Theorem, the relation of triangle angles and sides, and trigonometric functions?

Triangles are tied up with distance. Distance is important, so triangles are important.

Distance and the Shape of Spaces

Here is an unusual "triangle". It has three right angles, for an angle sum of \( 270^{\circ} \).

\(\angle{a} + \angle{b} + \angle{c} = \)°

The legs which meet off the coast of Ghana have the same length and are fixed at a right angle (the world map is just there to make the sphere's geometry intuitive). Change their length by entering an integer representing the longitude of the equator leg's endpoint, and the "hypotenuse" will move with them. Notice that for small leg lengths, the angle sum approaches the 180° that we're familiar with; this is what is meant by saying a sphere is "locally flat".

Clearly, this is not quite a triangle in the sense in which we've defined it so far. Triangle \( := \) A polygon composed of three line segments connecting any three points in the plane which are not colinear. Here's a broader definition. Triangle-y thing \( := \) A shape composed of the three shortest paths in a space between any three points in that space which are not on a the same path. (If you want to look more into it the shortest path on a surface is called a geodesic, and on a sphere the geodesics are called great circles. This is why, if you are used to the Mercator projection, you may be surprised to travel so near the Artic on a flight from New York to London.)

You know that if a surface is flat, the angle sum of a triangle is \(180^{\circ}\). The contrapositive is more interesting: if the angle sum of a triangle is not \(180^{\circ}\), it is on a curved surface.

Why should we care about spaces that are flat (Euclidean spaces)? Because they're easier.

The LIGO detector in Hanford, WA. Accessed here March 2021.

Why should we care about spaces that are not flat? Because not all physical geometries are actually flat. For example, when one is walking along a geodesic on Earth's surface, one cannot tell that it is not a flat line without travelling quite some distance: but, over long distances, failing to account for this will cause issues. Here is the LIGO detector at Hanford, a double example of this. It measures the warping, by gravitational waves, of 3D space away from its usual flatness. In order to do so, it needs long, straight arms at right angles; and, in order to build them with sufficient accuracy, its designers needed to account for the curvature of Earth.

Distance in Higher Dimensional Spaces and Image Interpolation

The Pythagorean Theorem extends straightforwardly to higher dimensions. In the following list, "d" means the distance between two points, and terms on the right hand side are the distance between the points on a given axis.

- 2D : \( d^2 := x^2 + y^2 \)

- 3D : \( d^2 := x^2 + y^2 + z^2 \)

- nD : \( \begin{eqnarray*} d^2 := \sum_{i=1}^n x_i^2 \end{eqnarray*} \) with n any positive integer

We cannot visualize higher dimensional spaces fully; the trick is not to try, and to let all the algebra chops we've been developing pay off. Trusting in the equations we've justified in dimensions we can picture, we can apply the methods of Euclidean geometry to such spaces, often with extremely powerful results.

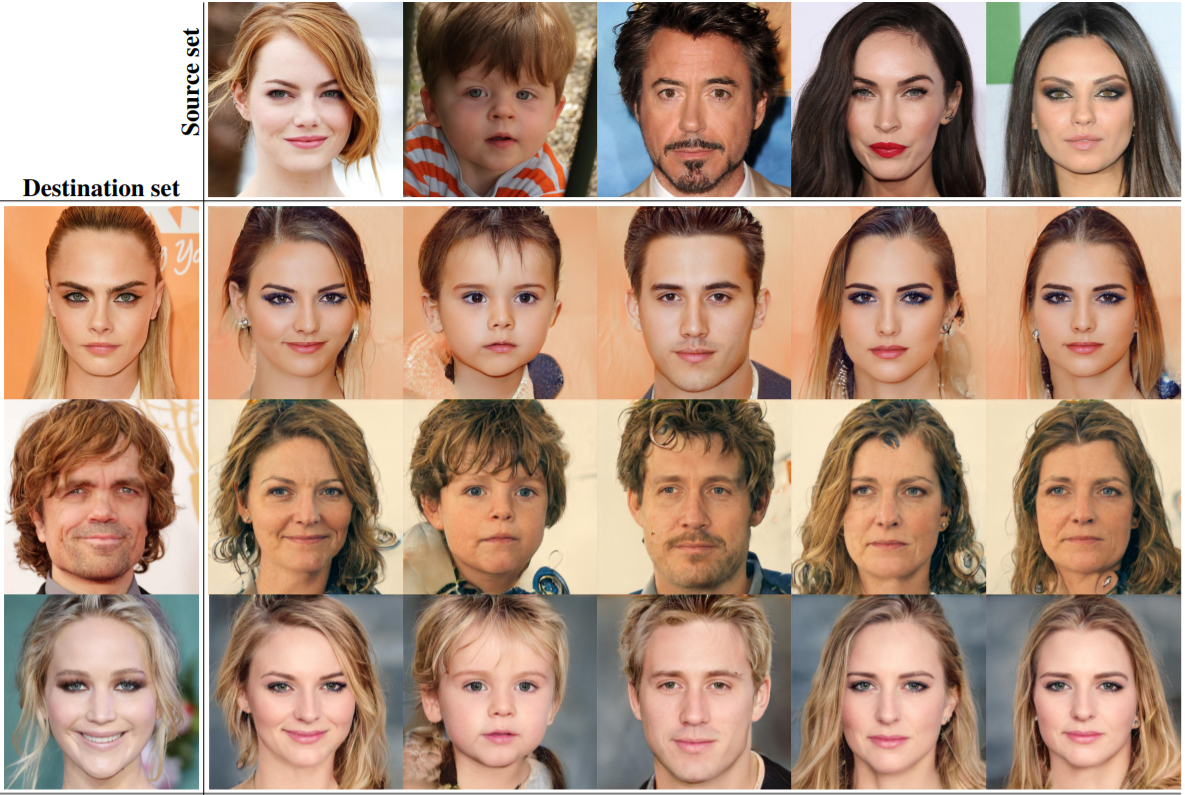

One such result is the ability to take the "average" of two images. We'll define the average of two points as their midpoint; encode the information of our image as a point in a Euclidean space, with entries representing say the pixel row, column, and color; and find the average of two images as the midpoint of their two points. Below is a very sophisticated example of image interpolation which nonetheless relies on the same concept of distance in some spaces; the difference is that these spaces encode more abstract information than just the colors of pixels.

Image interpolation from "Adversarial Latent Autoencoders" by Pidhorskyi et. al.

A very fancy algorithm that regards images and their properties as points in high dimensional spaces, and can do things like combine images or styles using Euclidean distance. We could build a usable image interpolator of our own with minimal code skills just by averaging image pixels' colors. The paper is here ; "Adversarial Latent Autoencoders", Pidhorskyi, S., Adherjo, D. et. al., April 9 2020