Applications of Symmetry

Symmetry is an ubiquitous topic in mathematics. It underlies many physical phenomena, and when symmetry is recognized in a problem, it often provides a much shorter way of solving the problem.

Symmetry \( := \) "A symmetry" of a collection of objects is an operation which, after it is performed, leaves the objects unchanged.

Many shapes are symmetrical, but it's not just about shapes, or rather, it's not just about literal shapes. By considering functions and/or data in a time series or along another axis, we can use the same geometric and algebraic techniques to reveal and understand patterns in many situations. I'll start with a literal shape: we can then understand the underlying geometry of the more abstract examples.

Section 1: Crystals

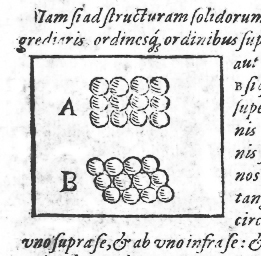

A page from Johannes Kepler's 1611 Strena Seu de Nive Sexangula

How are snowflakes so diverse, and yet so many have six sides? Why are table salt crystals, and many other mineral crystals, cubic? This question led Johannes Kepler to the first really solid (ha!) argument that matter is atomic; that it is built of building blocks which are, except in extreme physical circumstances, indivisible. By constructing large solids out of regular building blocks that lock together at regular angles, we can put the blocks together in any of quadrillions of ways, and still arrive at large shapes which are similar. Actually, this is what "crystal" means - a solid in which the constituent atoms are arranged periodically, ie in a repeating pattern. (Periodicity, which we study with the unit circle and trigonometric functions, is an instance of translational symmetry).

Symmetry transforms

r x° stands for rotate, m x° for mirror/reflect; these are the fundamental transformations of squares and hexagons that leave them unchanged. In jargon, the objects are 'invariant' under these operations, and the operations are called dihedral groups. Consider: infinite grids, which are practical for modelling the massive number of atoms found in periodic solids, have additional translational symmetries that polygons do not.

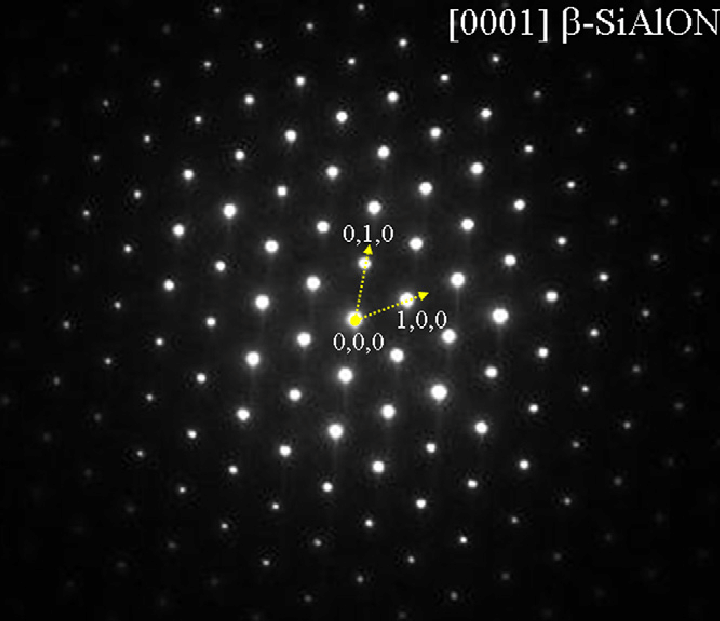

An X-ray diffraction pattern from hexagonal b-SiAlON. From "Identification of crystals formed in high lead glaze medieval Ottoman potteries by using microscopy techniques", September 2012, Turan et. al.

To get direct evidence of this, we shot X-rays through crystals, and got these patterns out the other side. These images are in some sense the geometric "inverse" of the actual arrangment of the atoms; still, the symmetry survives this transformation. (This is an example of an extremely powerful area of study called the inverse scattering problem, which describes optics, collisions, particle interactions, and much more). For the first time, atomicity was no longer a philosophical quandry: symmetry in X-ray projections closed the case.

Section 2: Rhymes

I have a theory about why sayings and songs that rhyme are more memorable than those that don't.

are semantic twine

when ends attach

the gists are matched

a single point

from thoughts disjoint

this makes a rhyme

a link in time

The rhyming lines have mirrored symmetry. In our heads, this attaches points in the story or case being made. The clause composed of the paired lines is percieved to have reduced complexity; the connection of two points is made for the price of one. In the same way one needs only a triangle to construct a hexagon, a rhyme builds up the semantic content of lines from a single anchor.

This same technique is used on larger scales. Rambling comedians or films surprise and impress us when they "bring it back" or "end where they began"; what seemed to be a freeform narrative now takes on a cohesion and purposefulness from the symmetry of the beginning and end.

Section 3: Conservation Laws / Noether

You've probably heard of the conservation of energy, of mass, and maybe of momentum. These laws can be explained by a beautiful mathematical truth identified by Emmy Noether in the early 20th century. Surprisingly, even the conservation of electric charge and other mysterious particle properties like quark color emerge from the same pattern.

In the graphic above, we identified symmetries as the invariance of objects under certain geometric transforms. The physical conservations laws correspond to the invariance of certain equations under coordinate transforms. From the fact that spacetime is invariant under change of space or time coordinates - it has translational symmetry in space and time - emerge the conservation of linear momentum and of energy. It makes intuitive sense to us that the laws of our world are homogenous, and further that they should not change whether we do math on them putting the origin here, or over there. As Neuenschwander puts it in Emmy Noether's Wonderful Theorem,

One such equation is the conservation of angular momentum of a system of bodies. The fact that the angular momentum is the same before and after some internal interactions does not depend on how we define our coordinate system:

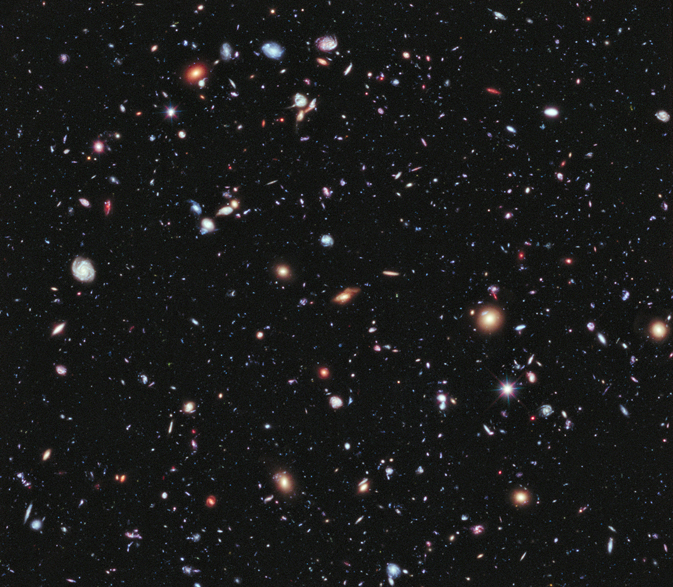

This conservation, by the way, is responsible for the fact that the bodies of our solar system mostly lie in a plane (the ecliptic), and why so many galaxies are disk shaped. A system of matter coalesces around its gravitational center; while the bodies lose kinetic energy through their many collisions, the whole system never stops rotating with the same angular momentum it had originally; thus what was a cloud appears to "collapse" into a disk.

Conservation of Angular Momentum and Spinny-Disky Things in Space

A Hubble deep field image of lots of spinny, disky things - galaxies, if you're a stickler.

Credit: NASA; ESA; G. Illingworth, D. Magee, and P. Oesch, University of California, Santa Cruz; R. Bouwens, Leiden University; and the HUDF09 Team. Accessed here March 2021