Mathematical Modelling

The Greek philosopher Zeno posed the following argument in the 5th century BC. An arrow shot at a target must travel half the distance, then half the remaining distance, then half of the distance remaining after that, and so on. Since (according to this argument) there is always another half distance to go, how can the arrow ever reach the target?

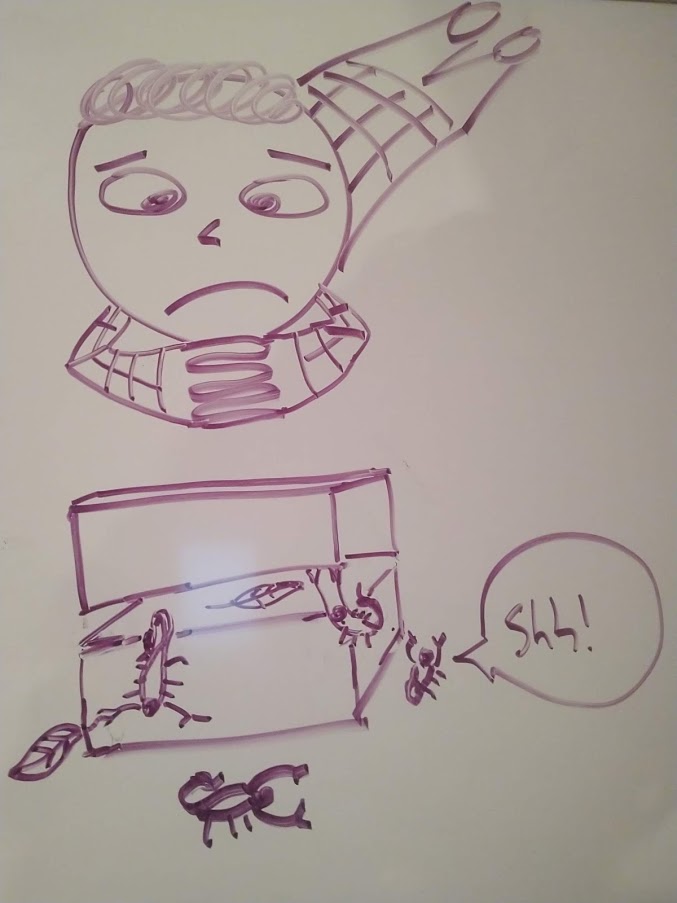

Major doofus Jan Baptist Van Helmont

It was once believed that small organisms formed spontaneously from nonliving stuff, ie fleas from dust. This was called "spontaneous generation". Jan Baptist van Helmont (1500's) helpfully determined that basil left between bricks in the sun would turn into scorpions.

These are examples of models, in particular bad ones.

I use "toy" not to belittle the importance of models but because they are ... things ... with behavior and state, little worlds of their own: toys, systems, mechanisms. They do not necessarily have much to do with reality besides being concieved within it. The rules of chess and the names of pieces are a model of chess play; the fact that someone could pick up a physical piece and eat it does not obey this model. A whole lot of poor reasoning is due to our conflating models with the things they model.

In order to test how well a model describes something, we must make observations and/or measurements of that thing. If the observations closely match what the model predicts, we say the model is a good model and give it a name, much like we would with a dog.

Let's start quantifying the accuracy of models with the following case study.

Section 1: Is this die a fair die?

In the gizmo below, roll a few times and ask: is this a fair die? Then roll a thousand, then a million times, and ask again. (Obviously the "die" here is a piece of code, which just changes the question to "did I write a fair die function"?)

Die behavior modelled with a uniform distribution

The purple bars tally the number of rolls of each value, while the green bars are fixed at equal numbers of rolls. This is called a uniform distribution, since the likelihood of each outcome is the same.

After a million rolls, you were probably convinced the die was fair. But hopefully your takeaway after just a few rolls was "I'm not sure, there is not enough data." This is the crux of our study of statistics: the merit of our assessment of a model depends on how much quality data we collect. This is why an anecdote is absolutely no grounds to, say, decide something about human nature. One needs lots of data to safely infer something about a system.

We'd like to measure how confident we are that the six sides of the die are equally likely - a model of the behavior of the die - which leads to the requirement of studying a little probability before statistics. To measure our confidence in that hypothesis (proposed model) requires us to ask:

Given that the hypothesis is true, how likely is it that the given data would be observed?

This motivates our study probability beginning in the next section.